INTRODUCTION

Historically, an Earth’s Surface Centric View has dominated military thinking about use of Space. Traditionally, that thinking has been couched in terms of offensive Weapon’s use against Surface-Based Targets; framed by the available technology: missile (conventional or nuclear warhead), laser, or kinetic object (a solid projectile). Space-Based Weapons have also been envisaged interdicting other Weapons in transit through the Earth’s Atmosphere, or in transit through Near Earth Orbit, before they reach a Target on the Earth’s Surface. Factors such as: (1) Increasing dependence on Space-Based Infrastructure, for command and control, communications, governance, economics, culture, and information storage; (2) Next (Sixth, Seventh, and Nth) Generation Fighters; and, (3) Increasing lethality of the Earth’s Surface, from Surface-to-Air, and Air-to-Air Weapons pushing Aircraft into increasingly higher ceilings, will radically flip the Conflict Paradigm from an Earth’s Surface Centric View, to a Space Centric View. A notional shift towards Space-to-Space conflict, and technological leaps, may likely see purely Space-Based conflict supersede conflict on the Earth’s Surface. This paper will look at a notional shift towards Space-to-Space conflict in terms of the emergence of a Space-Atmosphere Interfacing Theatre, and the notion of Spherical Tactics in Space.

THE SPACE-ATMOSPHERE INTERFACING THEATRE

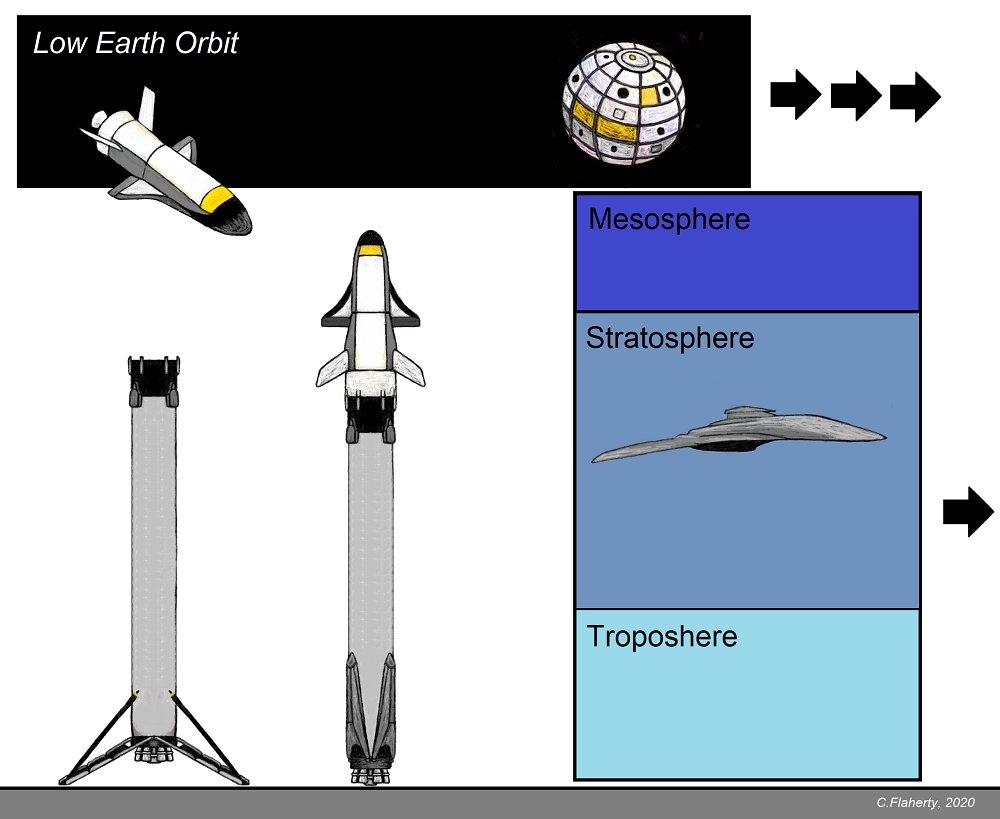

“FIGURE 1: Illustrates the Space-Atmosphere Interfacing Theatre. The Stratosphere is dominated by Next (Sixth and Seventh) Generation Fighters. The Low Earth Orbit and Edge of Space is dominated by Nth-Generation Fighters launched from Earth, or permanently based in Space.”

The major structural shift envisaged by this paper is the likely move from Space-Based Weapons used to attack a Target on the Earth’s Surface, to Space-to-Space Forces, designed to operate in a complex environment, attacking Targets in Space, in Earth’s Atmosphere, and on its Surface. It can be envisaged, rather than attack a High-Altitude Target, using Terrestrial-Based Forces, it is more likely – technically more effective, to attack from Low Earth Orbit. Tactical exploitation of Earth’s High-Altitudes, and Space, in the near and far-future is likely to structurally shift from a Theatre which extends into Space, from the Earth’s Surface (as it has been historically envisaged from an Earth’s Surface Centric View), replaced with development of the Space-Atmosphere Interfacing Theatre – comprising:

Terrestrial Box: The Terrestrial Box (see FIGURE 1), incorporates the Earth’s Surface, and its Atmosphere, to a flight ceiling defined by Extreme High-Altitude (where operational limits begin to express in the Stratosphere). Given current technology, a Military-Grade Air-Breathing Aircraft engine, in Level-Flight, can reach approximately 90,000 feet: 17 miles (27,432 meters: 27.4 kilometres), though historically much higher altitude records have been set by Fighter Aircraft, above the Earth’s Surface. For current technology, the Earth’s Stratosphere is too thin to support aeronautical flight at around 274,278 feet: 51.9 miles (83,600 meters: 83.6 kilometres). An Aircraft would have to travel faster than orbital velocity to gain sufficient aerodynamic lift.

Edge of Space: The notional Edge of Space (see FIGURE 1), roughly corresponds to the Earth’s Mesosphere, generally at an Altitude of 50 miles (80 kilometres) as the boundary, with a higher line at 76 miles (122 kilometres), where atmospheric drag becomes noticeable for a re-entering craft.

The Space-Atmosphere Interfacing Theatre presents a Complex Conflict Environment. Currently, Aircraft, and aerial combat operate in a zone covering low-flight, to the Mid-Stratosphere. New Horizon Technologies may change this dynamic:

|

AIRCRAFT (90,000 feet) |

|

BALLOON (173,900 feet) |

|

|

ROCKET PLANE (367,487 feet) |

Flipping, or inverting the current military paradigm from an Earth’s Surface Centric View, to a Space Centric View, focuses on combat space residing between Low Earth Orbit, and the upper reaches of Earth’s Atmosphere. As stated, will cause a major structural shift, from a traditional Theatre conception, where Space-Based Weapons are envisaged coming into effective range to attack a Surface-Based Target, largely in coordination with Terrestrial-Based Forces. It is possible, that a different conception can be envisaged from a Space Centric View of a Theatre, where objects move at a greater rate, than the Earth’s rotation.

Earth-Based surface-to-surface manoeuvre drastically changes where Space is used as the transit-route. For instance, as a basic principle a rocket craft can lift-off from one location on the Earth’s Surface entering Low Earth Orbit, can re-enter the Atmosphere at any location on another point on the Earth’s Surface at a much reduced timeframe, than that taken conventionally by an Aircraft. By way of comparison, the International Space Station orbits Earth about every 90 minutes, and over a 24 hour-period makes approximately 16 orbits of the Earth (during its rotation). The above analogy can be expanded to conceptualise a Theatre separation occurring, as orbit speed is greater than the Earth’s rotation, which represents a different view of the conventional definition of a Theatre, when Space-Based Forces are added into the mix. The conventional definition of a Theatre,

“[are its]… geographic bounds … extend to include the Space Forces … [and their use from Space immediately brings these]… in Theatre and legitimate targets … [by an opponent]” (Preston, 2002).

Space-Based Weapons, and Terrestrial-Based Forces have traditionally been viewed part of coordinated, and sequenced actions by diverse components set by a specific geographical context, underpinning the political aims of the conflict (Preston, 2002). Notionally, the Theatre is a geographical location where Terrestrial-Based Forces are available, or must be relocated to; and where Space-Based Weapons are brought to bear. This gives way to the notion of a constantly revolving planet, around which there are faster orbiting Space-Based Forces that can attack Targets in Space, in the Earth’s Atmosphere, or on its Surface (as these come overhead, and come into attack range). It can also be anticipated that in order to defend a portion of the Earth’s Surface, it does not necessarily mean that the Forces needed to do so, are located on the Surface. Instead these could operate at Extreme High-Altitudes, or operate from Space – the object being to attack Targets from above, from Low Earth Orbit. A progressive shift towards greater reliance on Space-Based Infrastructure, and increasing technological effectiveness and lethality of defending Terrestrial-Based Forces, could see much of the Conflict Environment shift to Low Earth Orbit, and its interface with High-Altitude Zones.

EARTH’S SURFACE CENTRIC VIEW

Historically, the Earth’s Surface Centric View has largely driven thinking about the use of Weapons. Engagement between Space, Atmosphere and Surface, historically has its emphasis on Surface impact, in one of four scenarios (see TABLE 1).

TABLE 1: Under the Earth’s Surface Centric View four scenarios govern use of Space-Based Weapons:

| SPACE | to | SPACE | Attack from Space, to a Target in Space |

| SPACE | to | ATMOSPHERE | Attack from Space at an Atmosphere Target |

| SPACE | to | EARTH’S SURFACE | Attack from Space on a Surface Target |

| EARTH’S SURFACE | to | SPACE | Attack From the Surface at a Space Target |

The traditional strategic value of Space-Based Weapons is their availability to attack a Target on the Earth’s Surface, at short-notice, or pre-emptively. For the last half-century, historical military thinking in regards to the use of Space-Based Weapons, have largely revolved around questions as to functions and tasks for which it is employed; and how its technical characteristics: similarities, differences, and constraints pre-figure the function-task equations. Questions about the viable use of Space-Based Weapons, have also sought to resolve conflictual problems around the relationship with Terrestrial (Earth’s Surface) Based Forces, the traditional: Sea-Based, Undersea-Based, Aerospace-Based, and Land-Based Forces. The traditional view of the relationship, is Terrestrial-Based Forces are used in unison with Space-Based Forces. Outside this, limited cases have been identified for using Space-Based Weapons in isolation, as a kind of extended Space-Based Weapons campaign, one that presupposes the relative logistic expense trade-offs have made these competitive with other types of Terrestrial-Based Forces undertaking the same functions-tasks (Preston, 2002).

Historically, a series of propositions have emerged in relation to the function-task uses of Space-Based Weapons, such as these are likely to be required where atmospheric or weather restrictions on Terrestrial-Based Forces necessitate use, or Terrestrial-Based Forces are not present to initiate a campaign. In the case of a Fixed Infrastructure Target, that is heavily defended, and high-value, a Space-Based Weapon could be an attractive option for a strategic attack. Space-Based Weapons may be the option reaching a possible Fleeting Target in time, provided its value is worth expending the weapon. In scenarios where using an Aircraft presents an unacceptable level of risk, a Space-Based Weapon could accomplish the attack (Preston, 2002).

Currently using Space-Based Weapons requires no international agreed covenant to use, and these are not subject to permission access, for transit, or for a Theatre Footprint to be established in a foreign country, in the case of traditional Terrestrial-Based Forces; which also require considerable logistical support and infrastructure to maintain. The counter argument against reliance purely on Space-Based Weapons is these currently have considerable logistical limitations, and leave-open the possibility that an opponent can ultimately develop an effective counter-strategy. The basic paradigm is that Terrestrial-Based Forces attack Targets within their reach, leaving the Targets out of reach to the Space-Based Weapons (Preston, 2002).

Space-Based Weapons, historically (and is still the case), are driven by extreme logistic costs, such as maintenance and replenishing costs. The economic realities restricts a Space-Based Weapon for use against a high-value or strategic Target; and, where there is no other option available. For instance, Surface-to-Air defences have not been suppressed, or basing and overflight rights have not been granted, or there is no broader allied coalition consensus on what military action, if any is appropriate. A Space-Based Weapon may come overhead at much shorter time-periods, giving it greater responsiveness. The intrinsic quality of Space-Based Weapons is use of these can shift from remote operations (in relation to the country of origin), to where little to no Terrestrial Forces are yet available, to use close-to-home. A Space-Based Weapon could multiply shock effects, if used in mass and concentrated attacks against a Target. If used for the first time, its unfamiliarity might also add to the shock. The agility and reach of a Space-Based Weapon might also be exploited to misdirect and confuse a defending Terrestrial-Based Force (Preston, 2002).

Underseas Considerations

Some 70.9% of Earth’s Surface is ocean and at the current level of technical development there are major constraints on the use of Space-Based Weapons against Undersea Targets, such as the ability to relay targeting information from acoustic sensors (Preston, 2002). While a Sea-Surface Target can be attacked, and vice versa a Space-Based Target can be attacked by a Sea-Surface Force, attacking an Undersea-Based Force, from Space – at the current level of technology presents greater difficulties. That being said, historically it has been the case that rockets have been fired into orbit, and near-orbit by Underseas-Based Forces.

SPACE CENTRIC VIEW

A Space Centric View, it can be argued, is primarily focused on two main scenarios: Space-to-Space, and Space-to-Atmosphere (see TABLE 2).

TABLE 2: Under the Space Centric View three scenarios, are likely to have greater emphasis in near and far-future conflict:

| SPACE | to | SPACE | Attack from Space, to a Target in Space |

| SPACE | to | ATMOSPHERE | Attack from Space at an Atmosphere Target |

| ATMOSPHERE | to | SPACE | Attack from the Atmosphere at a Target in Space |

At the current level of technological development, Space-Based Weapons have a high-level of strategic ubiquity; partly, because of the difficulty in defending against it. Increasing reliance on Space-Based Infrastructure, leads to wide-reaching national vulnerabilities; as does dependency on Space Systems to fight; and needing access to Space-Based Infrastructure to critically operate. In near-future conflict, using current technology, attacking a rival’s critical satellites or its satellite network could be used to isolate an opponent, blocking access to their technology to enclose and control them. The ability to destroy, suppress, frequency jam communications, command and control and early-warning systems may ultimately strip Terrestrial-Based Forces of any lethality. It can be anticipated, Space-Based Force development will focus on Control of Space, such as Counter-Space Capabilities: anti-satellite weapons, or cyber-attacking technology to damage, disable, deny, and tamper with access to critical Space support. Surface-Based Attacks will still be likely, used as the pre-cursers to an Attack in Space. Substantial attacks – possibly nuclear weapons strikes, could be seen on historically significant, and crucial space-port launch facilities. Concurrently, major attacks could target world-wide distributed ground-links, in many different countries well outside the notional Theatre.

Historically Space-Based Weapons have high logistical costs, and have inherently high time costs resupplying, and restoring used capacity (Preston, 2002). It is presumed Next Generation Space-Based Weapons will not only overcome reloading problems, but move from only delivering effects, “suitable for a relatively narrow range of targets” (Preston, 2002), to ones that deliver greater flexibility of use, precision, and selectivity. The responsiveness of a Space-Based Weapon is largely related to the issue of its lead-time for engaging a Target, that can range from tens of minutes to hours. For instance, a long deorbit time can mean attacking mobile Surface or Air (Atmosphere) Targets are not likely feasible (Preston, 2002). A more responsive Space-Based Weapon, shortens the decision cycle, and increases tactical control; and ability to integrate the use of a Space-Based Weapon with other Weapon options, such as: missiles, and conventional artillery. Improvements in the level of tactical granularity attacking a Target: such as the ability to destroy a basement Target only, and not the other floors (of a multistorey building), would see wider utility use of Space-Based Weapons. It is presumed that in the near and far-future that the design requirements of a Next Generation Space-Based Weapon would be to achieve instantaneous use, with a high-degree of sensitivity, and reach.

NEAR AND FAR-FUTURE NTH-GENERATION FIGHTER

The current near-future trend is development of Next (Sixth and Seventh) Generation Fighters. This paper posits an Nth-Generation Fighter. Much of this paper is based on a discussion citing capabilities which currently do not exist. It can be theorised, that in the near and far-future there will likely be a spectrum-shift from a Space-Based Weapon concept, to full adaption of currently Terrestrial-Based Forces, to comparable versions developed for a Space-to-Space Theatre. The technological drive towards development of an Orbital Space Fighter – conceptually the Nth-Generation Fighter, correctly sits at the juncture of a set of capability acquisition problems: what value add can a Space-Based option give over a comparable Terrestrial-Based version that can be used to attack the same Target on the Earth’s Surface, or its Atmosphere (Preston, 2002). The same question arises in relation to what options: Space, Atmosphere, or Terrestrial-Based, for engaging and destroying the same Target in Space.

The notion of developing a Single Stage to Orbit Spaceplane, or rocket launched piloted Manoeuvrable Aerodynamic Orbital Fighter have been explored in various concept-developments. The goal has been a craft capable of combat roles in Earth Orbit, and flying re-entry and landing on the Earth’s Surface (see FIGURE 1). The imaginary version illustrated in this paper, takes its inspiration from the original 1960-61 Mercury-Redstone Launch Vehicle, or later craft such as the 1973 U.S. Navy (DARPA) proposal for a manned combat spacecraft: Space Cruiser, launched into orbit by a modified Poseidon Missile Launch Stage. Return Flight Orbital Vehicles, have existed since the Space Shuttle Program, as does a current in-service First-Stage Returnable Rocket Lander. A notional mating of the two technologies illustrates how near-future technology could foreseeably prefigure a notional construct such as the Space-Atmosphere Interfacing Theatre. For instance, it can be envisaged that a cost-effective Nth-Generation Fighter, consisting of a Single-Stage Reusable Launch Vehicle (Returnable Rocket Lander), with a collar for supporting a Manoeuvrable Aerodynamic Orbital Fighter, could be used as the basis of a Space-Based Force, operating in Low Earth Orbit. Likely launched from a Heavy Mobile Launcher. The first-stage (which returns to land), and later re-joined by the fighter flying back to Earth; the design intended to reduce the high operating costs of space launches, incurred through waisted materials (see FIGURE 1). The Edge of Space portion of a near and far-future Theatre, could see in addition to the Returnable Craft, use of another type of craft permanently based in Space, either piloted, or robotic (or a combination force of both). In this paper – an imaginary Spherical Tactical Fighter (Spherical Spaceship) is used as a basis for looking at Spherical Tactics in Space (see FIGURE 2).

SPHERICAL TACTICS IN SPACE

The notion of tactics in Space are still nascent, as we do not know what technology will become usable in the near and far-future, that will ultimately come to drive tactics. Caveats can be applied to future envisioning of the likely form of space fighter tactics, namely constraints, such as the function-task equivalence between various technology options:

“to which they might contribute in-concert with other means of achieving the same functions and tasks” (Preston, 2002).

Constraints such as these are understood to override approaches, such as:

“simply basing doctrine on the general attributes of the space environment or adopting a custom from any other realm of experience.” (Preston, 2002)

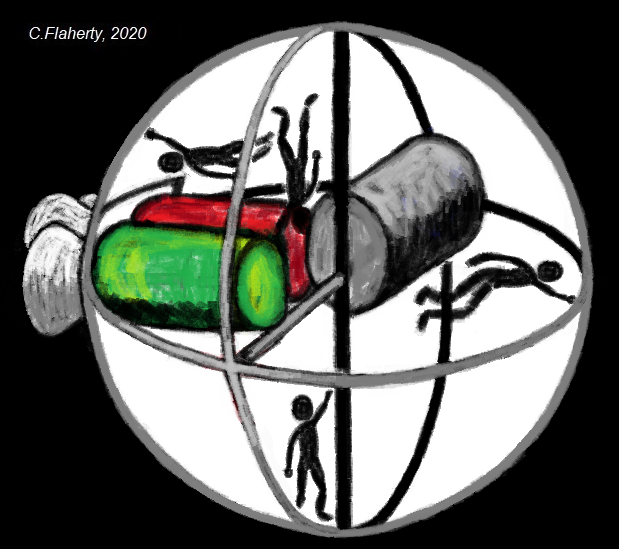

“FIGURE 2: The Tsiolkovsky Spherical Spaceship (Author’s version).”

However, ignoring the, ‘general attributes of the space environment’ altogether is equally problematic as any technology is going to be bespoke to operating in Space. At a fundamental level Space is a vacuum, and a boundless three-dimensional expanse where objects and events have relative positions and directions. That being the case, the sphere can be seen as a Tactical Shape: like the line, square, block, or triangle are all Tactical Shapes that have inherent tactical uses. The sphere emerges as a Tactical Shape, in light of the key attribute of Physical Space which is its intersection of three linear dimensions.

The Spherical Tactical Fighter (Spherical Spaceship): an Omnidirectional Craft, has been known since the Tsiolkovsky Spherical Spaceship (Tsiolkovsky, 1883; see FIGURE 2). The Tsiolkovsky Craft was envisaged crewed by four humans operating in orbiting weightlessness. Each occupant manned a facet controlling a different direction. The Spherical Spaceship has been a major trope in science fiction writing, and one of the more notable depictions of such a craft dates from the early 20th Century (Smith, 1928). Fictional use of a sphere as the basis of a craft operating in Space, serves as an interesting point of comparison, as to how we might envisage near and far-future Omnidirectional Craft (if these could be constructed), might tactically operate. The first intrinsic element, we note, its pilot has a panoptic view – in any and all directions. In the science fiction version, the craft is able to fix on a point in Space, from its point of origin in Physical Space, which is at the intersection of three linear dimensions. The second intrinsic element, from a combat view, manoeuvre, like the craft’s weapon capability, would be omnidirectional. In the fictional description, the craft has weapons pointing out into space in each quadrant, allowing for multiple directional engagement (Smith, 1928).

The notion of a craft permanently based in Space, designed as an Omnidirectional Craft capable of spinning, at its current location and acquiring a direction to attack, or able to attack in any, or multiple-directions simultaneously in Space is likely to be the end-point of future tactical development, and the design trajectory for future combat craft in Space. An Omnidirectional Craft notionally lends itself to the application of a spherical (three dimension) version of the OODA loop cycle: Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (Boyd, 1996). In this version of the OODA loop cycle, the pilot’s decision experience, occurs within a spherical – three dimensional framework, with multiple vectors, and decision points occurring in staggered succession, or several simultaneously. The spherical design of the craft, directly mirrors its pilot’s decision experience of space, translated into omnidirectional action by the craft, and its pilot. In short, the pilot thinks spherically, and the craft is designed for spherical tactics.

CONCLUSION

The current expectation is that in the near and far-future, the Atmosphere above the Earth’s Surface will effectively be a no-go zone, as Weapons become more effective, efficient, and lethal. Networked Aerial Combat underpins the current future vision. It is envisaged, that long-range Unmanned Arial Combat Craft will be coordinated by a human crewed bomber-size Aircraft with robust sensor suites operating deep in Enemy Airspace (Stillion, 2015). Likely outnumbered locally by defending Enemy Aircraft, this will be counteracted by Weapons capability to destroy attackers. Current generation Very-Long-Range Air-to-Air Missiles are effective at over 100 nautical miles, which will push-out potential Theatre boundaries. Refuelling Aircraft become more vulnerable to marauding Enemy Aircraft, operating sweeps of 500 to 750 nautical miles from their territory, potentially pushing the Theatre boundary by upwards of 1,000 nautical miles (Stillion, 2015). Future aerial combat is also expected to be marked by highly effective sensor-shoot capabilities, so rather than concentrate forces:

“future … aircraft may need to provide wide-area surveillance for themselves by operating as a large ‘distributed weapon system’ with sensors, weapons, and C2 linked by robust line-of-sight communication links … air forces in the early … [21st Century] … may find advances in sensor, weapon, and network technology make it unnecessary to ‘concentrate’ their aircraft to achieve mutual support.” (Stillion, 2015)

The rubrics of speed, and movement are central to future vision of aerial combat; however, a hawk will hover searching for prey below. Near and far-future conflict can be anticipated to take a number of iterative, and transitional forms, as technology leaps introduce new tactical options, arising from new propulsion, structural, and aerodynamic concepts increasing speed, ceiling, and manoeuvrability (Stillion, 2015). Avionics and sensors advances will continue to improve Aircraft’s ability to search for, and destroy Enemy Aircraft; and seamlessly transition from Air-to-Air to Air-to-Ground missions. However, future aerial combat could radically shift to a vertical plane in the Earth’s Atmosphere, to the Edge of Space, as technology options grow: the piloted command, or mother-ship could have the capacity to hover-in-place at High-Altitudes controlling at Lower-Altitudes long-range Unmanned Arial Combat Craft, operating at speeds, from subsonic to hypersonic. Materials that reduce radar signatures, or introduce stealth capability could be applied to even higher-climbing crewed command pods (with capacity for powered lift, and landing) suspended from High-Altitude Balloons, that perform the same function-task controlling a suite of unmanned combat craft.

It can also be anticipated that in order to defend a portion of the Earth’s Surface, it does not necessarily mean that Forces need to be located on the Surface. Instead defending Forces could operate at the Highest Altitude possible for currently flying Aircraft, or operate from Space – the object being to attack from above, in orbit, Targets located in Space, at High-Altitudes, and on the Surface. As a Conflict Environment, the Earth’s Surface will likely progressively diminished to the point of obscurity as defending and attacking Forces re-locate to the interface between High-Altitude Operating Aircraft (as long as that technology is relevant), and the Low Earth Orbit, where it is expected that near and far-future Space technology will develop new types of human-piloted, and robotic craft, some launched from Earth (and able to return), others permanently based in Space.

The historical scenario still holds true, namely attacking a Target, on the Earth’s Surface, Atmosphere or in Space will involve jointly coordinated, and synchronized Forces, making-up for gaps in coverage, by one Weapon over another. It must also be acknowledged a gap will always emerge between the technical-theoretical use of a Space-Based Weapon – simply matched to a Target as an isolated exercise, and real-world scenarios, where an opponent will independently seek counter-actions. This will likely see continued use of aggregations of Weapons allowed to overlap function-task equivalence (Preston, 2002).

A conceptual shift from an Earth’s Surface Centric View, to a Space Centric View will see a notion of Spherical Strategy in Space emerge as a transition from classical Asymmetric to Vertical Strategic and Tactical Dominance by one combatant over another (Flaherty, 2020). In this new paradigm, traditional strategy and tactics conducted on a planetary surface are radically inverted, to a new locus on the Orbiting Sphere surrounding Earth, its Moon, or other planets. The Orbiting Sphere becomes a strategic and tactical platform in its own right, marking a conceptual shift to Vertical Strategic and Tactical Dominance of the Terrestrial Surface. However, it should also be noted that as Underseas present limitations to the use of Space-Based Weapons, as Space-Based Forces become more dominant, a Next-Generation Underseas-Based Force may arise as an Asymmetric response.

- Boyd, J.R. 1996 The Essence of Winning and Losing. Briefing Presentation.

- Flaherty, C. 2020 Spherical Strategy in Space: Transition from Asymmetric to Vertical Strategies and Tactics (3 September). Available on Linkedin, or from the Author on Request.

- Preston, R. Johnson, D.J. Edwards, S.J.A. Miller, M.D. Shipbaugh, C. 2002 Space Weapons, Earth Wars. RAND Corporation.

- Smith, E.E. 1928 The Skylark of Space. Various Publishers. Project Gutenberg.

- Stillion, J. 2015 Trends in Air-To-Air Combat: Implications For Future Air Superiority. Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

- Tsiolkovsky, K.E. 1883 Free space. Manuscript.

AUTHOR

Chris Flaherty authored the Terrorism Research Center’s report – Dangerous Minds (2012). He was the co-primary author, along with Robert J. Bunker of the book – Body Cavity Bombers: The New Martyrs (iUniverse, 2013). Two essays of his, from 2003 and 2010 were reprinted in the Terrorism Research Center’s book – Fifth Dimensional Operations (iUniverse, 2014). He recently contributed a book chapter – The Role of CCTV in Terrorist TTPs, edited by Dave Dilegge, Robert J. Bunker, John P. Sullivan, and Alma Keshavarz, the book – Blood and Concrete: 21st Century Conflict in Urban Centers and Megacities, a Small Wars Journal anthology, published on behalf of the Small Wars Foundation with Xlibris (2019).

Dr Chris Flaherty https://au.linkedin.com/in/drchrisflaherty